“She said, they have to get rid of me, because they could have more problems.”

Download image

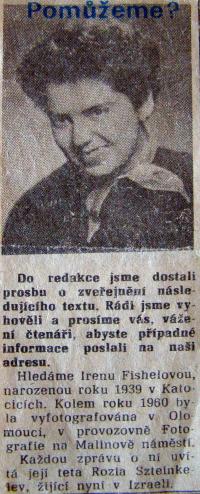

Irena Meixnerová (née Fiszlová) was born in 1938 in a Jewish family in Katowice. After the occupation of Poland by the Nazis, her father was deported to a labor camp, where he died. She, her mother and other relatives were moved to Sosnowies Ghetto, but her mother managed to escape from there with her and get to Vojkovice, Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. In Vojkovice, the mother left small Irena in Kohut’s family, but when she wanted to bring their other children, she was captured and tortured by the Gestapo. For the rest of the war, Kohut’s family was hiding her despite of a big risk. After the war, she studied an university in Olomouc, shortly taught at primary school in Mosty u Jablunkova and from 1962 until her retirement, she taught at the Secondary Techical School in Frýdek-Místek. At this school, she experienced also as a non-communist background check during the era of normalization. After the revolution of 1989, she met - for the first time since her childhood - her blood relatives, her cousins living in Israel. She also started to participate in meetings of the organization, Hidden Child.