The most important things in life are relationships

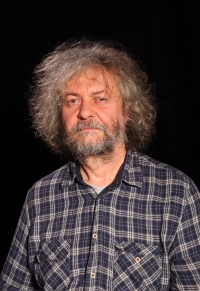

Vladimír Michal was born on August 4, 1961 in Banská Štiavnica in the family of Anton Michal (1932) and Daria Michalová, née Grečová (1938). Paternal grandparents Štefan Michal and Anna Michalová were born in the small village of Považský Chlmec near Žilina. They lived a simple village life, mowing meadows, digging potatoes, taking care of farm animals. Grandparents on mother’s side born in Banská Štiavnica. Grandfather Viktor Greč and grandmother Magdaléna Grečová worked at the municipal office and were actively involved in social life in culturally rich Banská Štiavnica. Both families of the grandparents were religious. Mother’s family participated in church festivities as well as the traditional Salamander festival, the tradition of which has been preserved in Banská Štiavnica to this day. Both families of the grandparents were religious. The family in Považské Chlmec did not perceive the war or the Holocaust as specific events, the Jewish population did not live directly in the village. Jews lived in Banská Štiavnica, but the family history does not remember the violent events of the deportations. There were people living in the city who were both positive and negative towards the Jewish population. After the war, however, it was obvious how many people were missing in the town. Grandparents in Banská Štiavnica remembered the SNP through people they knew from their surroundings, while not everyone who joined the partisans was considered a good person. They remembered the war mainly by crossing the front at its end, when first German and then Soviet soldiers passed through the territories they lived on. Both families housed officers and soldiers of both armies for a short period of time. When Vladimír was two years old, his father acquired a company apartment and they moved to an estate in Žilina, where he lived with his parents until he was eighteen. After kindergarten in 1967, he started elementary school. As a freshman he spent a lot of time in the school club (an activity after regular classes in the school premises under the guidance of female educators, note ed.), where the lady who was in charge of them read to them a lot from various books. The fact that cultured, educated and kind people took care of them back then, Vladimír still considers lucky and a very important thing for his future life. The day of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact troops, August 21, 1968, Vladimír experienced with his father and a neighbor on the mushrooms in Stara Bystrica. The adults noticed that there were unusual planes flying over their heads. After returning from the forest, they heard from the radio what had happened. They met tanks on the way home. Vladimir remembers these events as very traumatic for the whole family. Vladimir’s parents were passive opponents of the communist regime and tried to avoid everything that the regime did not expressly require. This is also why Vladimír did not become a spark (the first stage of the socialist youth organization, at the age of older pupils and students followed by pioneers and binders note ed.). When classmates took the pioneer oath, Vladimir was absent from school and therefore did not become a pioneer either. Vladimír went to grammar school in Žilina. He already had information about books and music that did exist but could not be accessed. He was greatly influenced by the Melodie magazine, which was not only about music and which he happened to discover at the PNS stand (newspapers and magazines were sold here, ed. note). He had a subscription to the magazine for several years, but after some time, under the pressure of the regime, the magazine changed its content so much that its original character disappeared and Vladimir stopped reading it. Membership in SZM (Socialist Youth Union) was perceived by Vladimir as a necessary evil, and activity in this organization was characterized by passivity. During his high school studies, Vladimír also worked in the local Theater of Small Stage Convergences Maják. Vladimír made his decision for further studies mainly with the aim of getting to university in Bratislava from Žilina, which was in the province at the time. Originally he wanted to apply for film direction at VŠMU, in the end he applied for the Electrical Engineering Faculty of the Slovak Technical University in Bratislava. During the first year, they founded a theater with their friends in the dormitory, the only play of which was marked as anti-state, so the theater ended in a short time. Later he also worked in the university club Primaf. At university, he met Juraj Kušnierik, who made a fundamental contribution to shaping Vladimir’s life. Sporadically, they came into contact with samizdat literature, they even created some samizdat themselves. Together with Janka, later Vladimír’s wife, they transcribed two volumes of Bondy’s History of Philosophy on a typewriter through typographical papers. Vladimír also maintained contacts with friends from Prague and Zlín from the underground environment. Through these contacts, he got access to other music, books and other samizdat. After finishing school, Vladimír married Janka and subsequently enlisted in the war. After returning from the military, Vladimír started working at the Research Institute of Computing Technology in Žilina, where they got an apartment. They managed to replace it and returned to Bratislava in 1989. They signed Několik vět. On November 16, Vladimír with Janka took part in a student protest in Bratislava, which ended at Hviezdoslav Square. They participated in the SNP square demonstrations, and soon after the revolution they started thinking about Artforum as a cultural organization and then a bookstore. These plans and their subsequent implementation completely absorbed them. The first public event of Artforum took place in the Shipmen’s House on February 19, 1990, where two bands performed and books printed in England were sold at Alexander Tomsky’s exile publishing house in London. They managed to get premises on Červená armády street number 7, where the first official Artfórum entered. He perceived the division of Czechoslovakia as a sad event. At that time, Artforum was already located on Kozia Street in Bratislava. Despite various obstacles, Artforum became a place for meeting people, launching new books and especially a place for the adventure of thinking, which, even after more than thirty years since its establishment, it remains to this day.