To help others, above all, and not live just for oneself

Download image

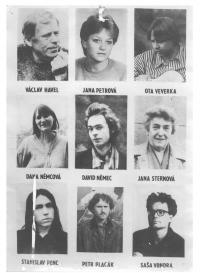

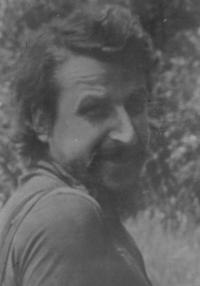

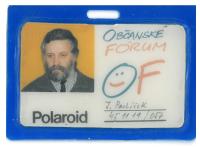

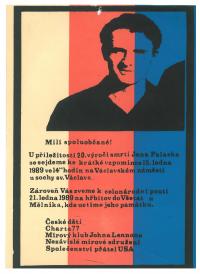

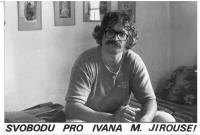

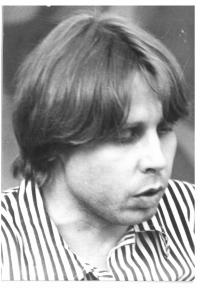

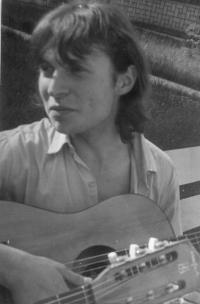

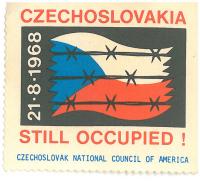

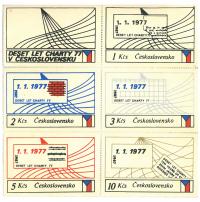

Jiří Pavlíček was born in November 1945 in Mělník. The family soon moved to Liberec to an apartment which had been abandoned by deported Sudeten Germans. When he was fifteen, Jiří became an alcohol addict and it took him the following twenty-five years to overcome it. He divorced twice as a result of his addiction and he was imprisoned two times. When working in the power plant in Horní Počaply he became acquainted with Heřman Chromý who became his lifelong friend and thanks to whom he began to get to know other dissidents as well. After Jiří’s second divorce, the authorities entrusted his daughter Adéla into his care. At that time he worked as an orderly in the hospital at Karlovo Square in Prague. In 1985 he won his battle over alcohol addiction, he signed Charter 77 and with the help of Petr Uhl he became actively involved in the dissent work. He was copying and spreading information on Charter 77 and various pamphlets and copying books. Together with other colleagues they established the Independent Peace Association and he helped with the organization of Symposium 88 and various demonstrations. He was summoned for interrogation many times and the authorities tried to intimidate him into emigrating from the country. After the Velvet Revolution at first he became involved in the Transnational Radical Party, then he established the Movement for Humanizing Healthcare and he served as a parish clerk in the protestant parsonage in Mělník, worked as an orderly in an institute for long-term patients and in a seniors’ home. Now he still continues with this work as a volunteer, and he also does volunteer work for the evangelical church.