In Theresienstadt nobody knew who would be first

Download image

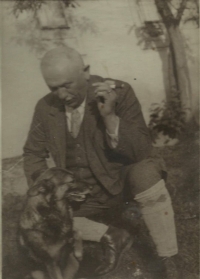

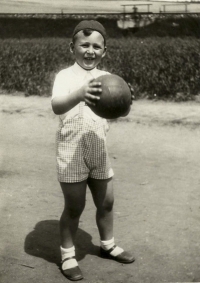

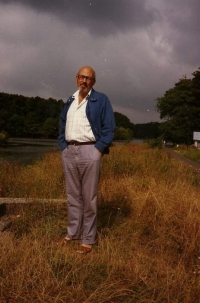

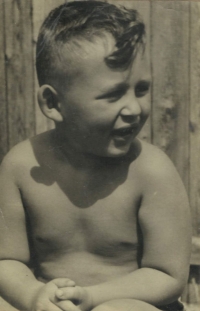

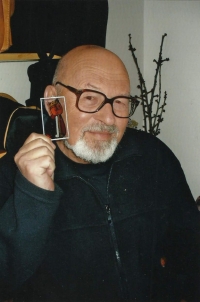

Pavel Pick was born on July 25, 1936, into a middle-class family that had roots in the countryside on both sides: mother Gertrude née Schmolková in Jablonná near Neveklov, father Emil in Dolní Bousov near Jičín. The parents were of Jewish descent but had a lukewarm attitude to religion. Pavel grew up in Vinohrady in a harmonious, loving family, he often went to his grandmother in Jablonná. After the establishment of the protectorate, they first tried unsuccessfully to emigrate, then the family was baptized, but unfortunately, it turned out that baptism did not protect them. The Pick family faced several racial restrictions, Pavel was allowed to play with other Jewish children only on the playground in the Hagibor area. He met many of his friends at the time in Theresienstadt, where the Picks were deported in January 1942. He was allowed to stay with his mother in the ghetto and later with his grandmother, his father lived elsewhere. The family was lucky, they managed to avoid transport to the east, unfortunately, grandmother Olga on his mother’s side was not so fortunate, she died in the Auschwitz concentration camp, as did grandfather Adolf from his father’s side. After the liberation, the Pick family returned to Prague, Pavel started going to school, quickly caught up with everything that was needed. Pavel was a good student, he studied medicine after graduation and became a doctor at the Faculty Hospital on Charles Square. He practised internal medicine and clinical biochemistry. In 1967, he received a scholarship from the Humboldt Foundation for research work in the University Hospital laboratories in Düsseldorf in what was then West Germany. During normalization, he was expelled from the Communist Party and affected by the ban on teaching. He worked at the Faculty Hospital all his professional life until his retirement and for several years after that, he also lectured to medical students at the university. In 1996, Pavel recorded a video interview for the USC Shoah Foundation, in which he tells in detail about three and a half years in prison in Theresienstadt.