We waited seven years for my father to return from the war. Then he was buried in a mine shaft

Download image

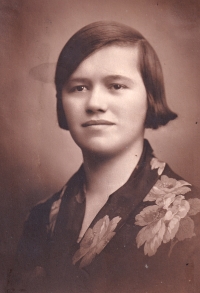

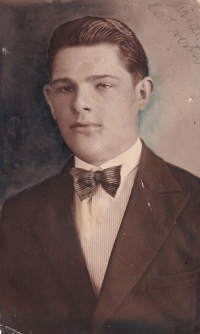

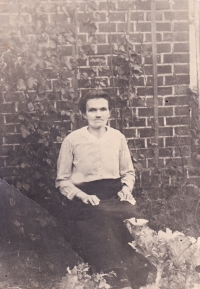

Renáta Plášková, née Kuczerová, was born on 11 December 1935 in Karviná. After Nazi Germany annexed Cieszyn Silesia to its territory, her father declared Silesian nationality and had to enlist in the Wehrmacht. He did not return until 1947. A few years later, he lost his life at the Barbora mine, where he started working as a miner after returning from English captivity. From an early age, Renáta had to help her mother with the housework and take care of her three younger brothers. During the war she experienced poverty. She saw the execution of German soldiers. At the end of the war, German and Soviet soldiers took turns in their apartment. She worked from the age of 15. Her first job was in a mountain chalet on the Červenohorské sedlo in the Jeseníky Mountains. She married Jindřich Plášek and had a son and a daughter with him. She cooked in the school canteen and then was employed in the Karviná cultural centre until her retirement. She was a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), but soon stopped attending meetings and was expelled from the party. In 2022 she lived in Karviná.