“They were very honest people, we didn’t have as good relationships with the Czech villages as we had with the German ones. And then Hitler came and it was all over.”

Download image

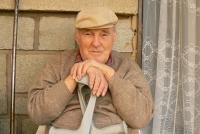

Josef Pojer was born in 1924. He grew up in Přísec near Jihlava (a Czech village near the so called Jihlava linguistic island). He comes from a framing family and he has six brothers and sisters. He wanted to become a mechanic like his brother Václav but his plans were interrupted by the war. After he was supposed to enter the job as a mechanic he had to leave to Germany as a forced labor worker. In February 1944, he left to Munich where he worked in the factory for aircraft components (BMW München). He was supposed to serve for tem months but he didn’t believe that. In July 1944, he agreed with his friend and two boys from Tábor to escape. It was a plan of four boys who worked together in one workshop. The boys from Tábor managed to escape, but he and his friend from Kněžice were caught on the run and taken to the police headquarters. Then they were returned to Munich and arrested. After the bombing of the corrective camp, Josef Pojer was transported to Dachau. The entrance medical examination was carried out by doctor Bláha. In Dachau, he spent six weeks which were left from his service and then he was sent back home. After the war, he worked in the Motorpal factory. He talks about plundering, the killing of a German neighbor, Mr. Bardas, and about doctor František Bláha, which gave testimony about the Nazi crimes at the International Court in Nuremberg.