“I retreated, but I didn´t surrender to the Germans.”

Download image

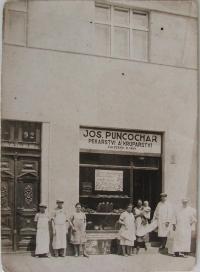

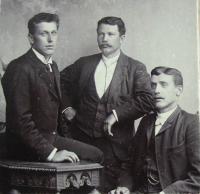

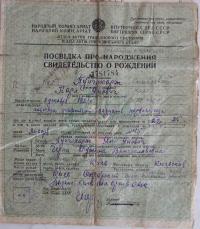

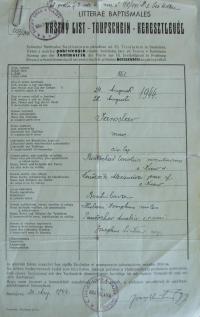

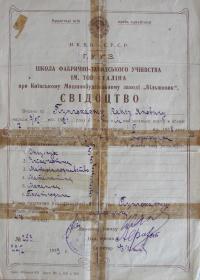

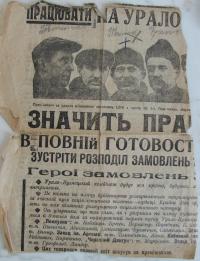

Mr. Karel Punčochář was born in Kyiv, Ukraine. His father, originally from a baker’s family, came from Kolín in central Bohemia, but moved to Kyiv in the pre-revolutionary times and settled down there. He died in the 1930s in a former NKVD prison (People Commissariat for Internal Affairs - translator’s note). Karel Punčochář - as a politically unreliable person - was placed into the 405th Special working battalion shortly before the war began. He spent the beginning of the war working on the construction of the concrete airport between Sambir and Lviv. After the Soviet Union was attacked by Nazis he retreated with the Soviet army troops. During another construction job he was taken prisoner by the Germans and placed in a collection camp, from which he managed to escape. He eventually legalized his citizenship in Kyiv and worked as a carpenter in a Bolshevik factory. Here, he met a Ukrainian woman named Alexandra. After the evacuation of the factory he moved to Krakow and from there to Slovakia. Together with Alexandra and their young son he was sent to Austria in 1944 to work on a farm. They planned to settle down in Bohemia (Kolín) after the war, but due to the fact that they were not married, Alexandra was deported as a Soviet citizen back to the USSR. Her son followed her five years later. Karel Punčochář has no recently information about them.