Working at the crematorium was my biggest underground

Download image

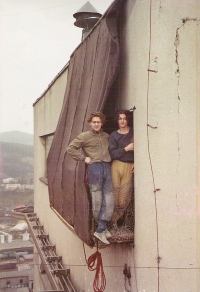

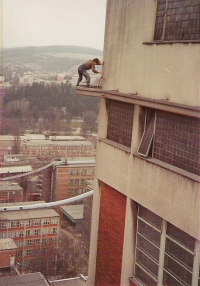

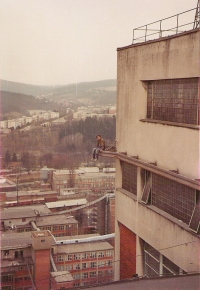

Jan Rozsypal was born on 27 July 1965 in Gottwaldov (today’s Zlín). In his early childhood, his parents divorced, and he went to live with his maternal grandparents Arnošt Michal and Františka Čuříks. At the age of six, his parents remarried, and Jan’s first sister was born. His second sister was born when he was 18 years old and already out of the house. His father, František, was very strict, and Jan never gained support or understanding from him. He grew up alone within the family and often escaped to books, reading as many as five or six in a month as a child. During his teenage years, he began to express his defiance and resistance to the typical norms of the time. He dressed eccentrically and started listening to rock and punk music. Then, in the mid-1980s, he stepped it up a notch and started wearing black, had his ears pierced, wore his hair up, and started wearing make-up. This brought him unwanted attention from the police, who often checked him because of his appearance. After graduating from high school, he began working in a stud farm, then in a hospital as a nurse of experimental animals. In April 1989, he joined the crematorium as an assistant stoker. He became friends with the Chartists but did not have time to sign Charter 77 himself because the Velvet Revolution came. In the spring of 1989, he signed the declaration Několik vět (Several Sentences - transl.) and distributed copies of it. In the same year, he took part in the demonstrations in Gottwaldov and welcomed the Velvet Revolution with great enthusiasm. In 1990, he worked on the repair of the famous Zlín skyscraper, the so-called Jednadvacítka (Building No. 21 - transl.). Between 2011 and 2016, he completed his higher education at Tomáš Baťa University in Zlín in the field of marketing communication. In 2022, he lived in Zlín.