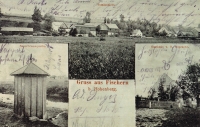

What hurts me the most is that Fischern is only on the map as a defunct village

Download image

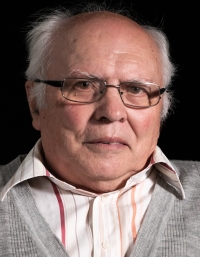

Erwin Rupprecht was born in 1934 in the village of Fischern, in the Cheb district. His father ran a mill on the banks of the Ohře River, which had been permitted to operate even during the war. Little Erwin loved being involved in all the activities around the mill. In the autumn of 1945 the property was confiscated and in January 1946 his family fled to Bavaria. The impetus for their hasty departure was the information that they were to be sent inland for forced labour. The nearby village of Bayerisch Fischern was to become their new home. The witness went to school in Hohenberg, trained at a weaving mill and had been working there for twenty-three years. He then worked for the railroad in Schirnding. As the Rupprechts’ former home was within sight on the other side of the river, they saw their house, mill and settlement being blown up in the early 1950s. The witness got married and has a daughter and a son. He was one of the founders of the Egerer Birnsunnta festival in Schirnding which he had been organising for years.