I felt deep sorrow for having been deprived of everything we used to have.

Download image

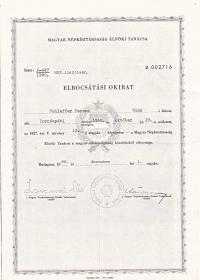

Ferenc Schlaffer was born in Pornóapáti in 1950. His native village was inhabited by mostly people of German ethnic origin. Also his family was of German origin, thus they spoke German language at home, too. His mother Anna Éder was a housewife who first worked in their private land, later in the cooperative. His father János Schlaffer was an indipendent smallholder for a while, later he got a job at the forestry. His family planned several times, first in 1956, to leave the country because of the poverty and the injuries they had to sustained. They lost their family house as well as a part of their land. Their plans to leave Hungary came to grief the second time in 1963 when the family wanted to live Hungary by the help of the father’s sister living in the United States of America. Ferenc Schlaffer has two sisters and a brother. His elder sister worked for the local cooperative, his brother had a job at the nearby quarry, his younger sister was engaged in Szombathely. Ferenc Schlaffer finished his schools in Pornóapáti and in the nearby village of Felsőcsatár. Then he went to Szombathely and he studied in an industrial school to be a skilled roofer. He finished school in 1968 and he was employed at Vasép (Iron Constructions) in Szombathely. He worked there for a couple of months, then he decided to leave Hungary just after he had turned 18. He returned home after a work shift, he handed over his wage to his mother and he directed himself to the border fence which was some hundred meters off their family house. He climbed up the fencing and jumped over to Austria. He could do it because Pornóapáti was limited by a defence system of double fences. Thus at the outer line of defence in the village itself there weren’t mines and there wasn’t electricity in the wire. On the Austrian side of the border Ferenc Schlaffer went to the border station, he was brought to Eisenberg, later to a refugee camp in Traiskirchen. First he wanted to go to the United States of America, but at the end he changed his mind and remained in Austria. Nevertheless he was officially banished from Austria for four years, he didn’t have to leave the country. He lived in Traiskirchen and he worked as a roofer in Wien. After a while he succeeded to move to Wien, too. He was given the Austrian citizenship in 1980 and he could visit Hungary at the first time after his emigration. He had an Austrian wife, but later they divorced. He lived together with an other Austrian woman and they had a child. His daughter Natalia died in 2005. In 1989 he remarried. His second wife is Erzsébet Gunyhó, of Szombathely. She works in Austria as a nurse while Ferenc Schlaffer has already retired. The couple lives both in Wien where they rent a flat and in Szombathely where they have a family house.