My brother said: ‘Hey, let’s swap’I said: ‘Hey, that’s not so easy

Download image

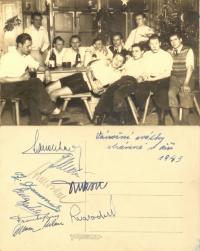

Jaroslav Svoboda was born on January 16, 1922. He had a twin brother Jan Svoboda and they lived together with their mother Anna Svobodová (maiden name Hovorková). Their father left them to seek “a better life”. Her mother worked as an assistant agricultural worker on a farm. Both boys became craftsmen - Jan became a lathe operator in the ČKD factory and Jaroslav made his apprenticeship in the workshop of a master locksmith. Since 1942 Jaroslav Svoboda was a forced-laborer in a factory in Graz together with some other 60 men from the Český Brod region. His brother was lucky as he worked in the factory and therefore didn’t have to go to work to the Reich. In the fall of 1944 they swapped in order to enable Jaroslav to visit his girlfriend in the Protectorate.