I went straight to work as a stoker so that the Bolsheviks couldn’t nag me

Download image

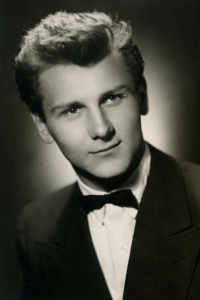

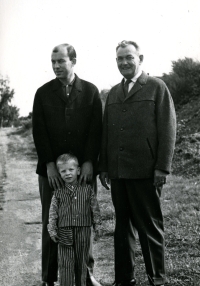

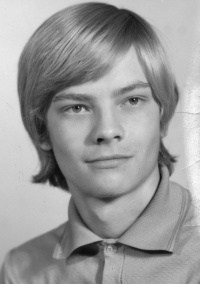

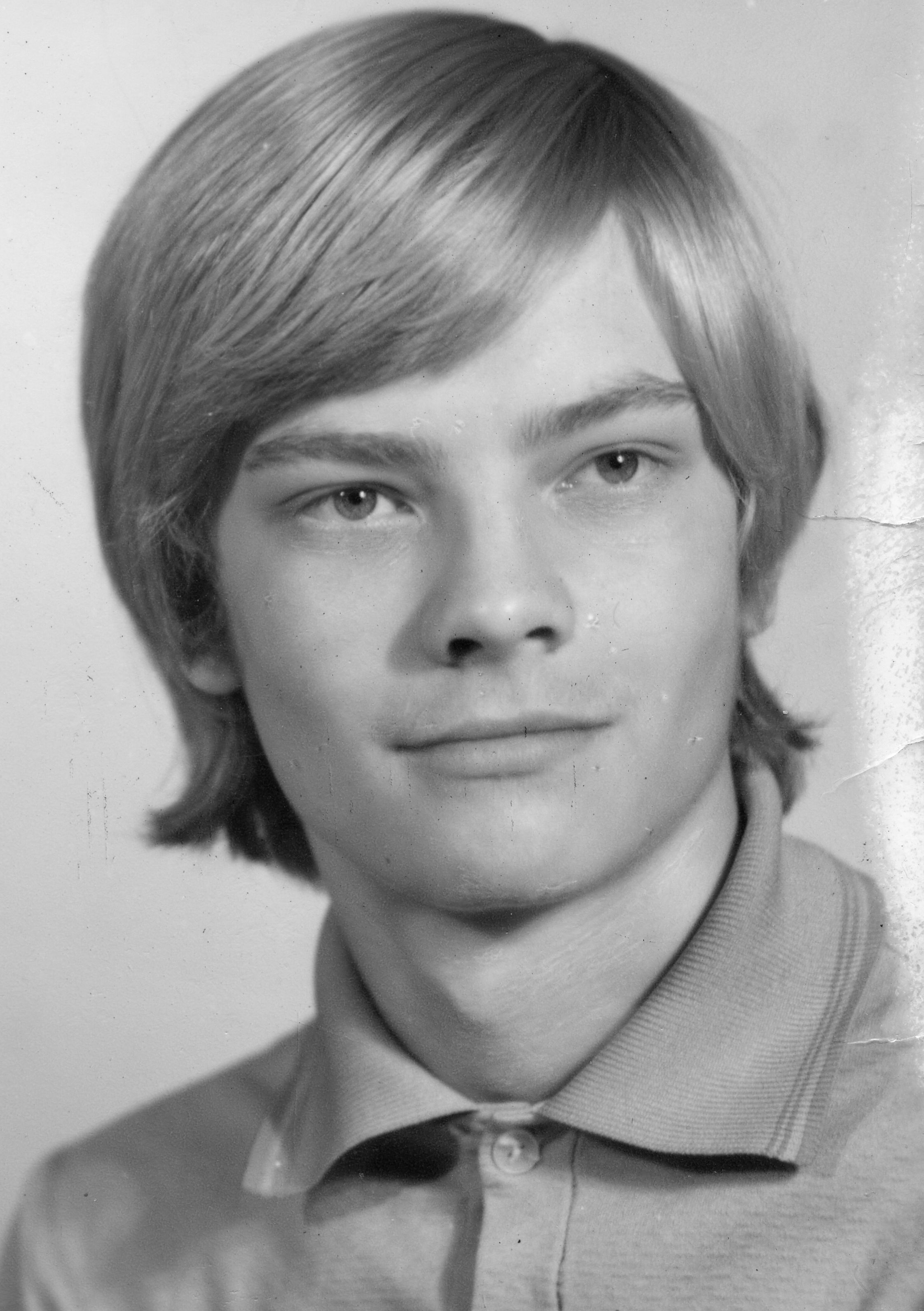

Miroslav Svoboda was born on 6 September 1962 in Hořice to Bohumila Svobodová, née Amanova, and Miroslav Karl Schmied, who lived in Pilsen. His father worked as a researcher at the University of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering in Pilsen, his mother taught mathematics and art at the primary school. After the war, the Red Army soldiers stayed with his grandparents in Nový Bydžov for a short time. Miroslav Svoboda started his schooling in Nový Bydžov in 1968 because of the August occupation, and continued in Pilsen. While studying at the secondary industrial school in Pilsen, he embraced the Christian faith. After his marriage to Libuše Táborská in 1981, the couple had sons Štěpán, Josef and František. He worked as an orderly in the University Hospital in Pilsen, a heating engineer in the Continental Hotel and in the blacksmith’s shop in Stráž, a lighting engineer in the Chamber Theatre and a pumper in the Vodní zdroje company. After five years of pretending to have a duodenal ulcer, he received a blue book. He ran a small home samizdat publishing house, copying a number of samizdat titles. The day before 28 October 1989, he was arrested with his young sons by State Security officers and interrogated, then continued to be followed. In 1989 he became the founder of the Civic Forum Pilsen and the Christian Democratic Party. In the 1990s he founded the civic association Exodus with Petr Žižka and later the unique website Scriptum. He studied theology and social work. At the time of filming (2024) he lived in Pilsen.