It was terrible. I thought we’d never make it to Prague

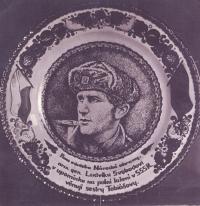

Lída Tarmesar, née Tobiášová, was born to a Czech father and a Polish mother on December 30, 1921, in the village of Makow (Poland). She was raised in an orthodox Jewish environment. Her father was poor but very well educated and not overly religious. After the German assault on Poland the family decided to flee to the Soviet Union. They were kindly received in the USSR and with the help of the Jewish community they were able to get all the way to Tashkent in Uzbekistan, where they stayed in a Kolkhoz. The Tobiáš family was rejected by the rising Polish army but with the help of a Jewish soldier, they were accepted by the Czechoslovak army and participated in the military training in Buzuluk. Her father died during the training in Buzuluk but her mother, her two sisters, two brothers and herself accompanied the Czechoslovak army on its march to Prague leading through Ukraine, Romania and Poland. As a switchboard operator and a corpsman she engaged in the battles for Kharkiv and Dukla, among others. She earned numerous decorations and medals. After the war she worked at the general staff of the Czechoslovak army and she was acquainted with General Svoboda. In 1949 she left the army service and went to Israel to help in the build-up of the Israeli army. In Israel she got married and changed her family name to Tarmesar. She lives not far away from Tel Aviv.