I detained the smuggler by mischance

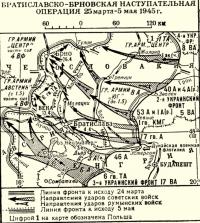

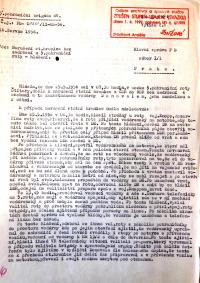

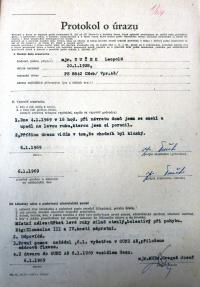

Download image

Leopold Tuček was born on 20 January 1928 in the little Moravian town of Lanžhot. His father was a blacksmith, and in 1933 he found employment in Hrušovany nad Jeviškou, heading a repair shop at the local train station. When the border regions were annexed by Nazi Germany, the whole family returned to Lanžhot. During the war Leopold finished town school and began an apprenticeship at the carpenter firm Hoffer. In 1944-5 he was sent to forced labour near Napajedla (with a short stop in the New Town of Vienna), and he took part in digging trenches in defence against the Red Army. In February 1945 he and other men attempted to escape, but they were betrayed and the Germans arrested the whole group. A month later he was more successful; he then hid in his native Lanžhot until the front arrived. He experienced the pitched battle for the liberation of the town. With the war over and influenced by a local family, the Babiňaks, who were active in both domestic and foreign resistance, Leopold Tuček joined the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. A year later he participated in the national party conference in Prague. That same year he completed his apprenticeship at the Valtice firm Ševčík, and with the help of the chairman of the Local National Committee, he joined the National Defence Corps (NDC, the state police). In 1949 Leopold Tuček was drafted for compulsory military service. At first he served in Bruntál at the 2nd Artillery Regiment, but as a member of the NDC he was soon transferred to the border guard sections. In autumn 1949 his squad was sent to Hazlov in the Aš District (the westernmost tip of the country). After undergoing a course for physical training officers in Prague, he served the company in Libá. In the summer of 1951 the border sections of the NDC were reorganised into the Border Guard (BG). In 1951-2 the witness attended the military vocational school of the Border Guard in Prague. He attained the rank of Staršina (Sergeant Major) and took command of the company in Nový Žďár near Aš. Shortly thereafter, the barber Bodor, a seemingly firm comrade, but apparently in fact an agent of the CIC, deserted from his company and escaped into West Germany. The escapee then talked of his service in Radio Free Europe, and mentioned his commander, Leopold Tuček, by name. This “interest from the other” brought Tuček a relocation to the border with East Germany. Here he served as company commander in Dolní and Horní Paseky. He subsequently attended a school for mid-level commanders in Bruntál. At the rank of Captain he then served at BG boot camps in Vojtanov, Cheb and Luby. For a long time he was one of the few commanders of the 5th Brigade of BG Cheb who was not a member of the Communist Party. He did not join the Czechoslovak Communist Party until 1960, under pressure from his superiors. In 1968, at the rank of Major, he was serving at the BG training centre in Aš. He was Chief of Staff of the 2nd Battalion when the country was occupied by the Warsaw Pact armies. He was not active in the so-called renewal process, but he retained his position even after the Communist Party vetting. During the 1970s and ’80s he took part in the development of the Aš branch of the Svazarm organisation (Union for Cooperation with the Army). He helped create the local Svazarm shooting range. He retired in 1985, but continued working as an operative for special tasks at Aritma until 1988. Leopold Tuček lives in Aš to this day. He has been married since 1954, he and his wife Věra brought up two daughters, Mirka (1955) and Věra (1958).