Two Czechs came and asked about my father. Little did I know that they were the Gestapo

Download image

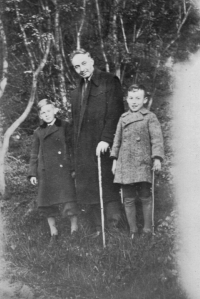

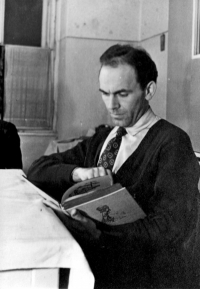

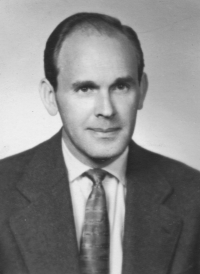

Oldřich Vašák was born on June 24, 1926 into the family of the Czechoslovak legionary František Vašák. He grew up in Moravský Krumlov, from where the family moved out in 1938, when the town fell within the Sudetenland. At that time, Oldřich was studying at the military gymnasium in Moravská Třebová in the Hřebeč region. He recalls the conflicts between the local German-speaking Germans and the soldiers. After the occupation of Czechoslovakia by Nazi Germany, the school was shut down and Oldřich returned to Brno, where he later studied at the business academy. In June 1944, his father was arrested by the Gestapo for his participation in the Czechoslovakian resistance. He died in the concentration camp in Litoměřice six months later. At the end of August 1944, Oldřich had to enter forced labor in the Diana underground factory, where he manufactured Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters. The arrival of Red Army soldiers foreshadowed another evil for Oldřich when he witnessed their violence. He perceived the Communists as enemies throughout his life. He found a job position as the head of the accounting department of the Faculty of Education, which fell under the rectorate of Masaryk University, where he worked until his retirement in 1987. Oldřich moved back to Moravský Krumlov. In 2020, he had a “stone of the disappeared” placed in front of his birthplace for his father František Vašák.