Every generation must learn the craft of patriotism

Download image

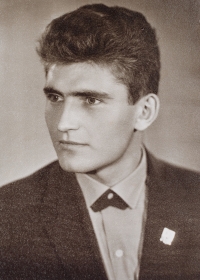

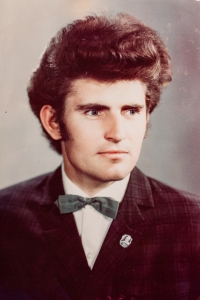

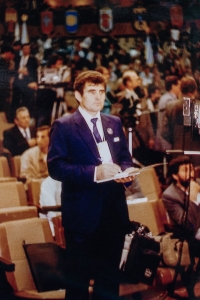

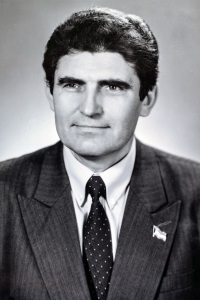

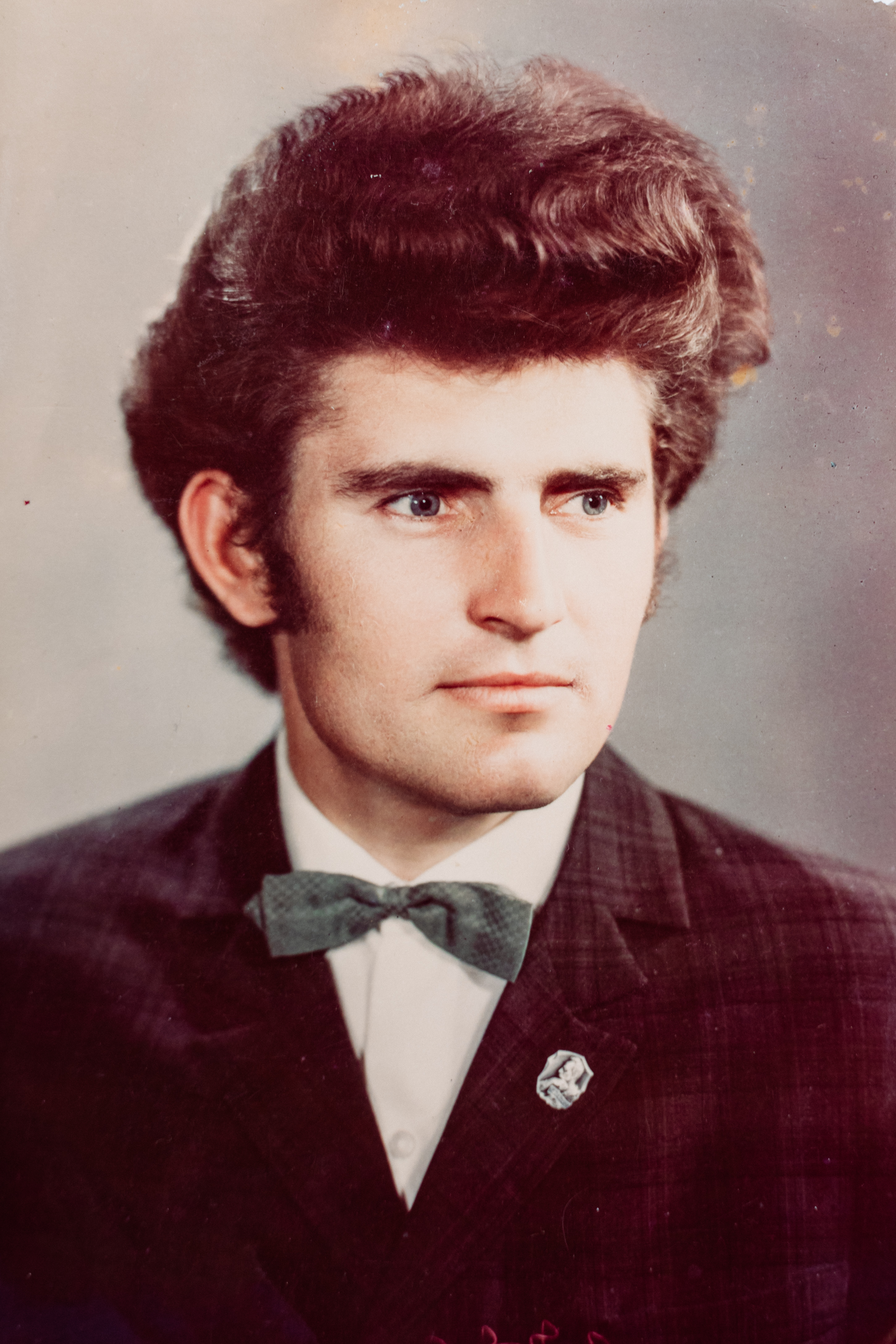

Sviatoslav Vasylchuk is a journalist and activist of the People’s Movement of Ukraine. He was born on September 5, 1941, in the village of Antonivka, Rivne region, in a family of underground members of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. After graduating from high school in 1958, he went to the Donetsk region, where he worked in a mine. In 1964, he entered the Kyiv State University, Department of Journalism. For his active participation in the student protest against the Russification of education and the poor level of teaching, in 1965, he was sent to the labor collective for “re-education” and later, in 1966, expelled from the university. In 1968, he moved to Uzbekistan, where he worked as a correspondent for the regional newspaper Pravda Kashkadari. In the 1970s, after returning to Ukraine, he worked for the newspapers Korchahinets, Radianske Podillia, and Vinnytska Pravda. He was forced to resign from the latter newspaper as the editorial staff began to put pressure on him after learning that his father had fought against the Soviet regime. After moving to Zhytomyr in 1978, he became the editor of the Ukrinagroprom Center. From 1989 to 2003, he headed the regional organization of the People’s Movement of Ukraine. From 1990-2002, he was a deputy of the Zhytomyr Regional Council three times. Since 2000, he has been the head of the Zhytomyr Regional Association of the Taras Shevchenko All-Ukrainian Society “Prosvita”. In 2015, he was awarded the Order of Merit III degree. He is engaged in educational and social activities.