“I dictate to everyone that I was born with trains, but I have no idea who I got it from ... probably from grandpa, he was some track inspector.”

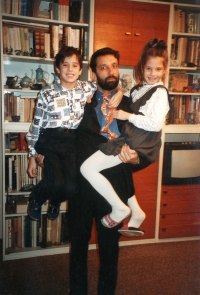

Tomáš Votava, was born in 1965 to parents from Prague. Blanka and Ferdinand met for the first time in the school canteen of the Prague University, the “Academy of Performing Arts”, where the mother studied graphics and father played the cello. This great love of theirs culminated in a wedding in 1957, as well as the arrival of two boys, Aleš and the younger Tomáš. As shortly after the wedding, Tomáš’s father received a job offer in the Slovak Philharmonic, it was already more than probable that a move to Bratislava would follow. It was completely natural that their family was spoken in czech, and therefore that he and his brother also learned czech language. He learned slovak only when he was seven years old, but he already had relatively good slovak during his kindergarten attendance. Most of Tomáš’s childhood was made up of trains. It’s a matter of the heart, a hobby, but most of all it’s something that still fascinates him. After primary school, he decided to go to the Secondary Industrial School of Transport in Trnava. He later became a train dispatcher, although he always wanted to be a train driver, which was never allowed due to poor eyesight. He has never had a serious problem with being Czech. He was accepted by slovak society and as a little boy he does not remember any allusions. Perhaps later, at an older age, he occasionally heard ethnographic speeches from supporters of the SNS political party. He also remembers when he had to go to the slovak authorities, for the so-called “Certificate of nationality”. At present, Tomáš has two children and a beautiful, several-month-old granddaughter. He moved away from trains in 1994 and became an expert in retouching and scanning, which he realizes for a certain magazine to this day. He still loves trains, but only in his free time, which he spends on websites about trains or on trips to different countries which are full of railroad machines.