My mother didn’t survive the war, my adoptive parents saved my life

Download image

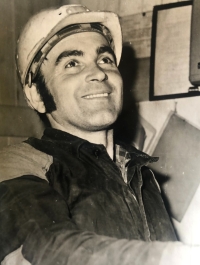

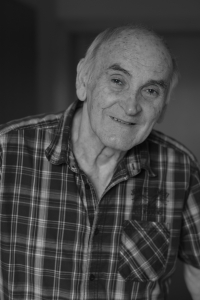

Vladimír Dvořák was born as Vladimír Kuzmenko on 5 February 1943 in Berlin to Ukrainian Halya Kuzmenko. She was a forced laborer in Germany during World War II. After the Allied bombing in 1943, young Vladimir and his mother were moved to Rokytnice nad Jizerou in the Giant Mountains, where a labor camp was established. Due to the harsh conditions, Halja fell ill with tuberculosis and died in the hospital in Jablonec nad Jizerou on April 9, 1945. The memoirist witness was in danger of his life. With the help of doctors and neighbours, he was saved by his adoptive parents, Mr. and Mrs. Dvořák. They waged a long struggle for his adoption and acquisition of Czechoslovak citizenship. He grew up in Tříč. Vladimír Dvořák trained as a moulder, worked in a foundry and, despite his severely damaged hearing, also in a mine in Harrachov. He married in 1965, has two sons and lives in Rokytnice nad Jizerou. He was widowed in December 2021.