“One had no idea what democracy or freedom was.”

Download image

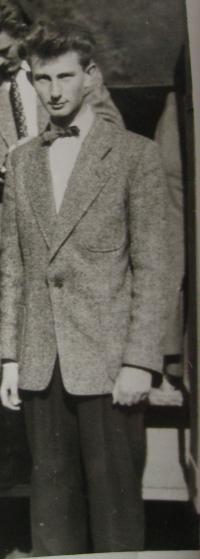

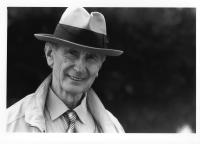

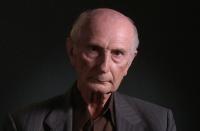

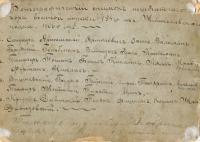

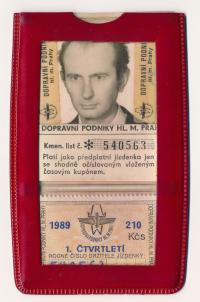

Ing. Vladimír Hajný was born in 1939 in České Dorohostaje in Volhynia. In 1947, he re-emigrated to Czechoslovakia with his mother and sister. His father, a war veteran, was given a farm in Šumperk. Vladimír completed studies at the University of Agriculture in Prague. He was strongly influenced by the leftist views of his father and in 1964, he became a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. He, however, lost his ideals in 1968 and left the Party after the invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies. In 1973, he began publishing a samizdat magazine titled Res Publica. He was interrogated by the STB due to his contact with his friend Čestmír Vaško, who had emigrated to West Germany. In 1984, he signed Charter 77 and after the initiation of Perestroika in the USSR, he became actively involved in the activities of the dissidents. He took part in several demonstrations aimed against the communist regime. In August 1988, he was brutally beaten by an STB major, JUDr. Zdeněk Šípek, during a demonstration on Národní Street. In 1994, Vladimír was the chief witness in the court trial against Zdeněk Šípek, who was sentenced to 14 months of imprisonment for the abuse of authority by an official person. At present, Mr. Hajný is retired and lives in Šumperk.