They murdered his grandfather, his uncle, aunt, and two cousins including a ten-year-old girl

Download image

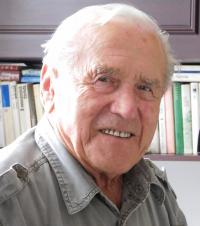

Viktor Hnízdil’s birth certificate claims that he was born on 28 February 1928 in České Kneruty in the Dubno Governorate in Volhynia, which was Polish territory at the time. In actual fact, he was not born until the spring of that year, and his date of birth was erroneously recorded during the post-war remigration to Czechoslovakia. Those nigh on twenty years that he spent in Volhynia left an unforgettable mark on his life. He experienced both the Soviet and the German occupation, the mass slaughter of Jews, and the terrorising of local inhabitants by Banderites. As a fifteen-year-old boy he was assigned to a so-called stripka, which was a Ukrainian law enforcement service instated by the Germans. In his line of service he experienced repeated clashes with the Banderites and several narrow escapes from death. He was also an eye-witness of the burning of the neighbouring town of Český Malín. Among the burnt and shot bodies of men, women, and children were also his grandfather Josef Mišák, his uncle and aunt Viktor and Emílie Mišák, his sixteen-year-old cousin Josef Mišák and his only-ten-year-old cousin Lilie Mišáková. When the Soviet forces arrived in 1944, his father joined the Czechoslovak army corps and served in the intendance (supply) unit all the way from Dukla Pass to Bohemia. In 1947 the whole family remigrated from Volhynia to Czechoslovakia and settled down near Šumperk. In 1956 Viktor Hnízdil married Jaroslava Johnová - the couple moved to Bedihošt, where the witness worked as a garage supervisor at the local sugar refinery for many years. In 2004 the Hnízdils returned to Šumperk. They still lived there in 2016.