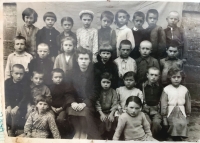

We joined the collective farm in 1949, [it was] one of the last ones. I don't know why it happened, but we were not persecuted, our family. My grandfather knew Russian, he went to teach at school — there were not enough teachers in the first grade to familiarize him with the alphabet, with the Bukvar [ABCs]. And then the military came, they were wearing side caps, military uniforms, [they were] Ukrainians. They were already teaching, and he became the school's storekeeper. He gave away his ploughs, this and that, to [work] at the school… [such things] were happening in all schools. Well, in short, the school was fine, the teachers were good, at that time, they... the war was over, they were military — they entered pedagogical institutes [universities] in Tiraspol, Odesa, in parallel they were studying extramurally and taught us and, of course, the school was weak. But they taught us to read, and they filled up quickly, they filled libraries with books. And this reading, I'll tell you, it aroused the spirit of competition. And the lamp was kerosene, and your eyes already hurt, and at night you sit and finish reading because you have to give this book to your classmate tomorrow. Well, in short it was beautiful, lovely, peaceful. And after the war everything was somehow being restored, restored. And it was much calmer and richer in Bulgarian villages than in the entire Ukraine. The war had passed there. And here, the war had passed through — the Romanians and Germans came in 1941. And they chose our house for some reason. We had a big room in our house, very big. And one German said, "Let's call the girls and make a dance party." They set up a huge gramophone, and these German records, you know, when you drop them, they break. I've forgotten what song it was, God. What was the name of this song that was popular at that time, German. They danced there in that house and left. And three or four years later, the Soviet regime arrived. And one of my (he died) relatives, Dimitr Peychev, an artist from Chişinău, from my village. And so he came one day and said to our grandfather, цell, the family is big — there are a lot of old people. He says, "Well, what are you going to do?" I said, "Well, I want to be a pilot." — "And you?" — "A painter." — "[You should] come and paint my fence." He became a national artist. And died. And a portrait of one of the tsars was drawn in pencil at their request. And I remember how an NKVD officer came in, looked, "And who is this?" My grandmother said, "It's the tsar, I think." He left, and we didn't get [repressed]. Because such things, that is, we were lucky, our village. Because the times were tough back then. And there were people who, well, how can I put it, there were people who wanted to be recognized, who wanted to distinguish themselves, to fulfill the plan. So they were mowing [repressing people] left and right.