What was the worst was the burning of Czech books.

Download image

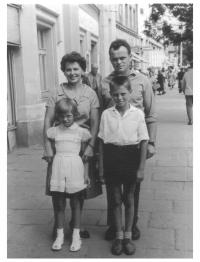

Marie Vrhelová was born October 21, 1929 in Albrechtice in the Šumava Mountains. She spent most of her life there or in the nearby town of Sušice. Before the war, the village of Albrechtice was inhabited by both nationalities, with Czechs having a majority. Their peaceful coexistence came to an end before the outbreak of WWII, when the local Germans, influenced by the Nazi propaganda and Heinlein’s movement, began to stir conflicts. The problems culminated by the German takeover of the village and the entire border region. Moreover, Marie’s father was arrested by the Gestapo and he spent nearly five months in prison in Kašperské Hory. When he returned, the formerly healthy man had almost no teeth, and soon after he was sent to do forced labour in Germany. Marie was likewise ordered to go to work in Germany, but after some time she escaped from her duty and returned home. On her journey home she experienced she found herself in Nurnberg during the air-raid on the city. She experienced first-hand all the problems of the era: firstly, the takeover of the borderlands and the activity of the local Germans, then the dreary war years and subsequently the liberation and the cruel treatment of the defeated Germans. After the war she married, moved to Sušice and she spent most of her life working as a manager of the local cinema. In her narrative she recalls events both comic and tragic.