We are alive, we are together again, we keep fighting

Download image

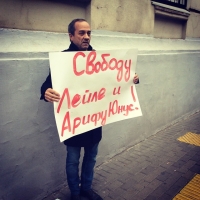

Arif Sejfulla ogly Yunus was born on 12 January 1955 in Baku, in the former Azerbaijani SSR. His father’s parents were shot dead after a show trial in the 1930s. His mother’s parents fled collectivisation into Nagorno-Karabakh at the same time. Arif studied history and postgraduate studies at Baku State University, and served in the Azerbaijan Academy of Sciences. In his first year at university, he formed a youth organization, the “Union of Like-Minded People”, whose purpose was to return the USSR to the correct path of socialism, from which Arif believed it had strayed. He was arrested in 1976 for alleged anti-Soviet views, but was released two and a half months later. Arif married the future human rights activist Leyla, and together they wrote their dissertations, articles for the samizdat newspaper Express Chronicle, and read banned literature. Since 1988, Arif has been chronicling the events of the Armenian and Azerbaijani pogroms that were at the beginning of the conflict between the two countries. In 1992-1993 he headed the Information and Analysis Department of the Office of the President of Azerbaijan. In 1994-1997 he was the representative of the humanitarian organization Caritas in Azerbaijan. Since 1997 he has been a staff member of the Institute for Peace and Democracy, founded by his wife Leyla Yunus. He has written more than 200 articles and several books on the current situation in the Caucasus and Nagorno-Karabakh, religious, ethnic and military conflicts and refugee issues. He was arrested in 2014 and accused of being an Armenian spy. He was tortured in an Azerbaijani prison but no confession was extracted from him. In 2015, a court sent him to prison for seven years for alleged economic crimes, but under pressure from the world community his sentence was changed to a suspended one. In 2016, Arif was granted political asylum in the Netherlands, where he lives with his wife Leila and daughter Dinara. Together with his wife, he wrote the book “From a Soviet Camp to an Azerbaijani Prison”. He continues his human rights activities with the Institute for Peace and Democracy, which is now registered in the Netherlands. Arif Yunus was in Prague in late August and early September 2022 at the invitation of the Forum 2000 Foundation, to whom we are grateful for arranging this interview.