I have been moving all my life. I’m a lifelong displaced person

Download image

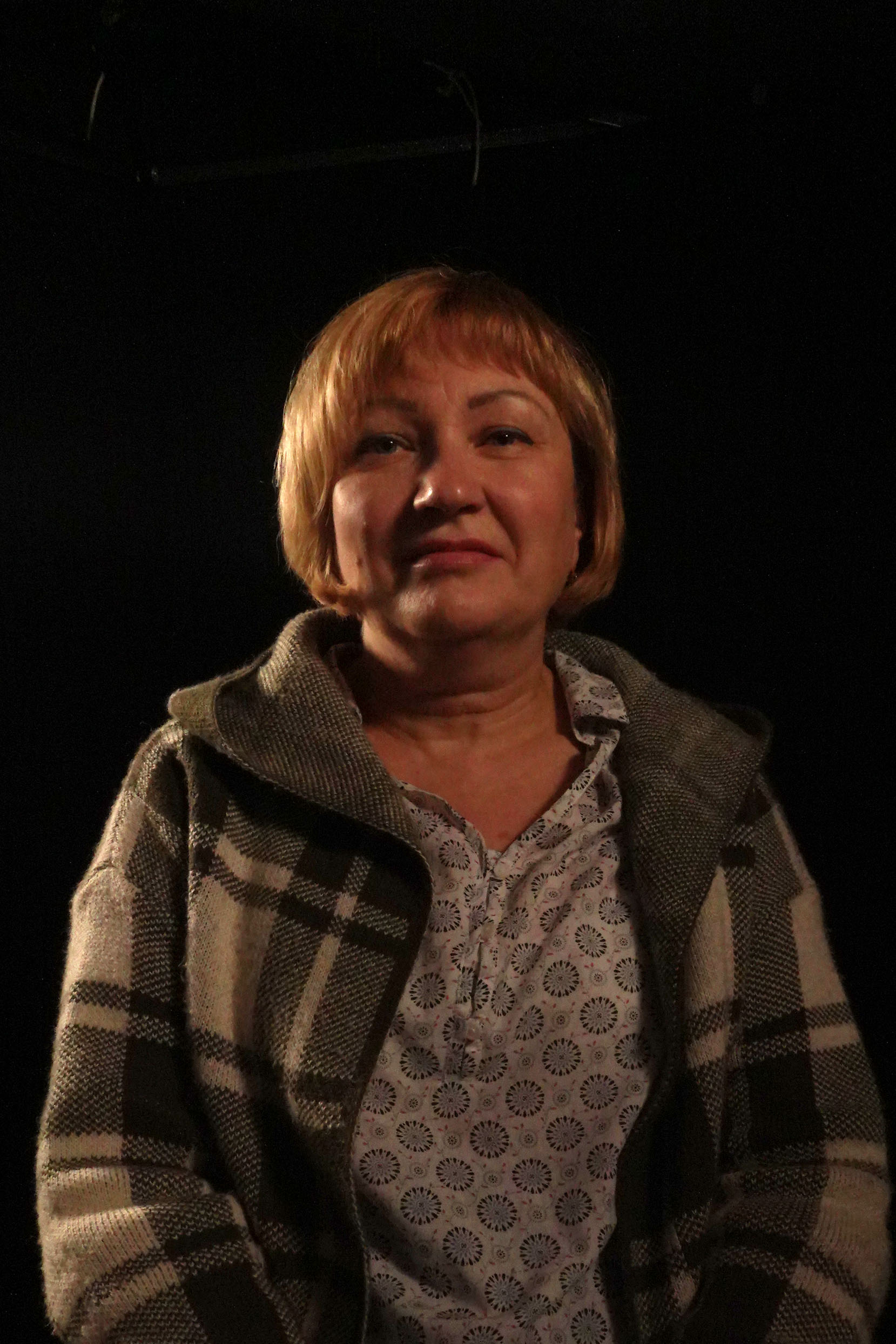

Maryna Demko is an employee of an NGO that helps Ukrainians affected by the war. She was born on July 11, 1969 in Donetsk. Her parents were immigrants from Russia. In search of a better life, the family moved to Norilsk in the north of the Russian SSR in the mid-1970s. Maryna studied at a pedagogical college in the city of Igarka. In 1989, she gave birth to a son who developed deafness, probably due to a poor-quality antibiotic. In 1994, Maryna moved to Makiivka, where her son was able to study at a boarding school for deaf children. She worked at the Makiivka City Water Utility, where she rose from secretary to head of the labor protection service. On May 8, 2014, when the battles for Kramatorsk were underway, her second husband, Oleksiy Demko, was taken prisoner by the self-proclaimed “DPR” for his participation in the preparation of the presidential elections in Makiivka. Maryna was forced to flee the city because of the threat to her life. With the help of her husband’s fellow party members, she tried to ransom him. After his release, she got a job at the Donbas SOS NGO. In 2015, Maryna and Oleksiy Demko moved to Kramatorsk, where they started a business and joined the work of the Free People Employment Center, a non-governmental organization dedicated to facilitating the social adaptation of IDPs, veterans, and other vulnerable groups. In 2024, she lives in Kramatorsk and works remotely for Donbas SOS.