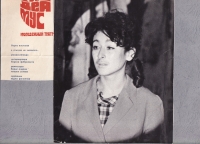

I Became a Jew at the Age of Forty

Download image

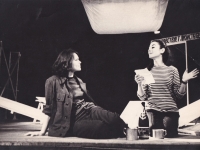

Adel Dianova is a Ukrainian Jew, theater actress, and public figure who has been the longtime head of the all-Ukrainian Jewish charitable foundation Hesed-Arieh. She was born on May 22, 1948, in Lviv, which had only just begun to integrate culturally into the Soviet Union. During her school years, she wanted to be a ballerina and studied at the Higher Theater School in Moscow, yet due to her father’s disapproval of her decision, she returned home before graduating. She later graduated from the Polytechnic Institute in Lviv with a degree in mechanical engineering. However, her passion for theater never left her, so, following her dream, she spent her entire life on the theater stage, acting in the Gaudeamus Theater from 1975 to 2007. She was a student and colleague of directors Anatolii Rotenshtein, Borys Ozerov, and Roman Viktiuk. In her mature years, Adel Dianova definitively discovered her Jewish identity. In 1998, she became the head of a foundation that pioneered social work in the West of Ukraine. She participated in a number of projects related to Jewish history and culture. She is the organizer of the international festivals of Jewish books, music, and theater, Vohnehryvyi Lev (The Fire-Maned Lion), Suzirya Leva (Constellation of the Lion), and LvivKlezFest. She lives in Lviv and continues to work on the development of Ukrainian-Jewish relations.